Now this really looks like an alligator!

/Marie Catrett is back with another glimpse into the world of children’s learning and growth at Tigerlily Preschool in South Austin. Marie is inspired by Reggio Emilia and informed by her deep curiosity and many years of experience working with young children. This guest contribution is adapted from one of her regular letters to Tigerlily families.

5/4/2023

Marie writes:

Today is a fine example of how we can help children think more deeply about their work and loan them the use of our skills in a way that helps them grow their own.

Marie (as we’re headed into the classroom, to R, a young three-year-old in our group): I have a question I want to ask you, about the alligator you made in clay yesterday.

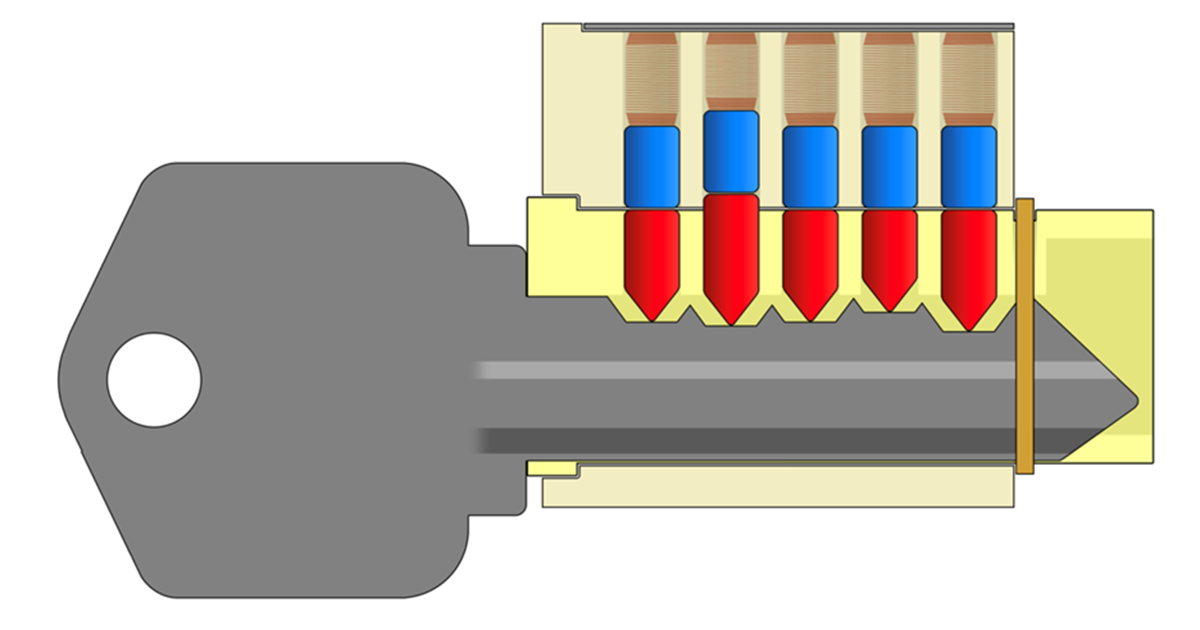

R’s alligator is a flat face figure, with drawn-in eyes and a cheerful mouth, and this piece stands up because he added a nice big tail at the back in response to my asking, “Can you think of anything else your alligator needs?”

Today we look at Alligator together. It’s so charming as is, and doesn’t necessarily need any further embellishment if R doesn’t want to go further, but maybe . . .

Marie: Here’s a question I have for you. I notice you drew the alligator’s mouth, and I wanted to ask you something. May I look at a picture of an alligator with you?

We look at some pages from a well-known current story in our group, Mrs. Chicken and the Hungry Crocodile.

Illustration by Julie Paschkis, in Mrs. Chicken and the Hungry Crocodile, by Won-Ldy Paye and Margaret H. Lippert.

Marie: I’m wondering (this is me asking children about their work, are you satisfied?), sometimes people make an alligator and it feels important to show about teeth. It’s up to you (me, really working hard to make a yes or a no thanks be acceptable here, the maker truly is in charge, but the opportunity to add a meaningful detail is always exciting to me!), but if you’re interested in adding teeth to your alligator, that’s something we could think about together.

R looks at the pictures and announces that yes, his alligator needs some teeth.

My co-teacher, Lulu, has the excellent idea that it might also help to go look at the toy alligator that’s been such a popular player in the classroom this week.

From earlier in the week: the wild animals birthday party, no wilding allowed.

Re: no wilding allowed at the party, the alligators take a meeting.

Ah ha, looking back at play this week, it makes sense that thinking about alligators has been on R’s mind, enough to want to make one with the clay.

And while looking at images can help kids think more about what they want to do, touching an example of what they’re thinking about is even better.

R explores the mouth of the alligator. His first “face” alligator is also in the frame above.

I am imagining helping him add bits of clay to his drawn mouth line to make the wanted addition of teeth happen, but R now has a richer vision of how to make this alligator more alligator-y.

R: I think an alligator should have an open mouth. And teeth. And a tongue that sticks out.

Marie: Hmmm. Wow. Okay. Oh! You know what, when my potter friend Jane came to show us about how she uses clay, she said starting with a pinch pot is a great way to make creatures. Would you like to try that?

Yes, says R, and we get a small ball of clay out to begin with a pinch pot. When it’s big enough, and turned on its side, R sees the shape he needs to decide it’s an open mouth. He adds eyes on top by drawing them on, in the way he’d done on the “face” version.

Marie: I heard you say about teeth. I can think of two ways you could add those . . .

I take an extra bit of clay and show him some options to think about. You could use the tool to draw them in, as he’s done his eyes. Fingers could pinch up some teeth bumps maybe? Or . . .

Marie: These are just to show some ideas, but you’re the maker, so it’s up to you what you’d like to do.

R likes the idea of using his fingers to make “teeth shapes” out of clay. He places them where he thinks they need to go on the mouth, and I help him make them attach securely.

Marie: You know what, I bet you could also make a tongue shape like you’re wanting.

From left to right: R’s first and then second alligator.

As we’re looking at the finished work, an older child says, with admiration, of the second piece: “Wow, now this really looks like an alligator!”

One of my favorite things about striving to be a Reggio-inspired teacher is working with children like this:

I hear your interesting idea.

Let’s think more about this together.

I see a way that I can be a resource for what you’re wanting to do.

Here are some options to think about what feels right to you.

What do you think?

And, are you satisfied?

Marie Catrett | Tigerlily Preschool