When a trowel and a wooden spoon are just what the doctor ordered

/From Austin to New York, parents are putting a nutrition curriculum, healthy cooking lessons, and time spent in vegetable gardens at or near the top of the list of things they want their kids to learn in school, and many alternative and public schools, as well as government programs and nonprofits, are filling that need.

I wanted to look at the variety of ways students are getting important nutrition information, and I can tell you one thing: This is not your mother’s Experiences in Homemaking class from the 1950s, nor is it my Home Ec class from the 1970s. It’s much tastier!

Our alt ed community has long been active in emphasizing holistic learning, including healthy eating and gardening in daily school routines. For example, last year the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine awarded Austin’s Integrity Academy a “golden carrot” for its commitment to serving plant-based, organic meals. In the short run, commitment to students’ health means more energy and attention in the classroom, but in the long run it also means less risk of disease in adulthood. At Integrity Academy, kids spend a lot of time nurturing plants in the garden and learning to eat mindfully, enjoying the peas, squash, beans,and other crops they’ve grown themselves.

Another Austin school dedicated to “building community through the power of food” is Wholesome Generation. The Reggio Emilia curriculum at Wholesome Generation serves low-income families and encourages kids to join in all the activities around meal preparation: “Let them be part of the gardening. Part of the shopping. Part of the prepping and slicing and dicing. Get them confident in the kitchen.”

In Texas, alternative schools led the way in bringing nutrition education and cooking into the curriculum, but now AISD is making big strides as well. With a Good Food Purchasing Program that includes sustainability, animal welfare, fair farm labor, and nutrition in its considerations when sourcing food, AISD is improving the quality of breakfasts and lunches served to students. Many of the veggies in those meals now come from the Garden to Café program, started last year at six Austin-area schools where kids can now plant, harvest, and eat their own greens. Another source of yummy, local food for Austin schools is Johnson’s Backyard Garden.

Nearby, in San Antonio, the Culinary Health Education for Families (CHEF) program, launched this year with funding from the Goldsbury Foundation and supported by the Children’s Hospital of San Antonio, is getting serious about children’s health. The program is setting up teaching kitchens for students at the YMCAs, Boys and Girls Clubs, and even the San Antonio Botanical Garden, as well as partnering with local public schools.

Across the continent, in New York City, Yadira Garcia is among many professional chefs working in the innovative Wellness in the Schools program, a growing nonprofit that now reaches about 50,000 students in New York, New Jersey, California, and Florida. The chefs teach cooking classes and nutrition during the day and create special events involving parents after school. In a recent New York Times article, Garcia noted that the key is for students to make the meals themselves, so they “turn into the best salespeople,” encouraging their friends to try the kale chips, black beans, and salads they’ve created.

A for-profit New York City enterprise called Butterbeans is run by two moms who were looking for a way to bring healthy food and wellness education to students in a playful way. In addition to providing lunches to about 15 schools in the city, Butterbeans also offers camps where kids can learn to grow and cook their own food while exploring urban gardens around the city.

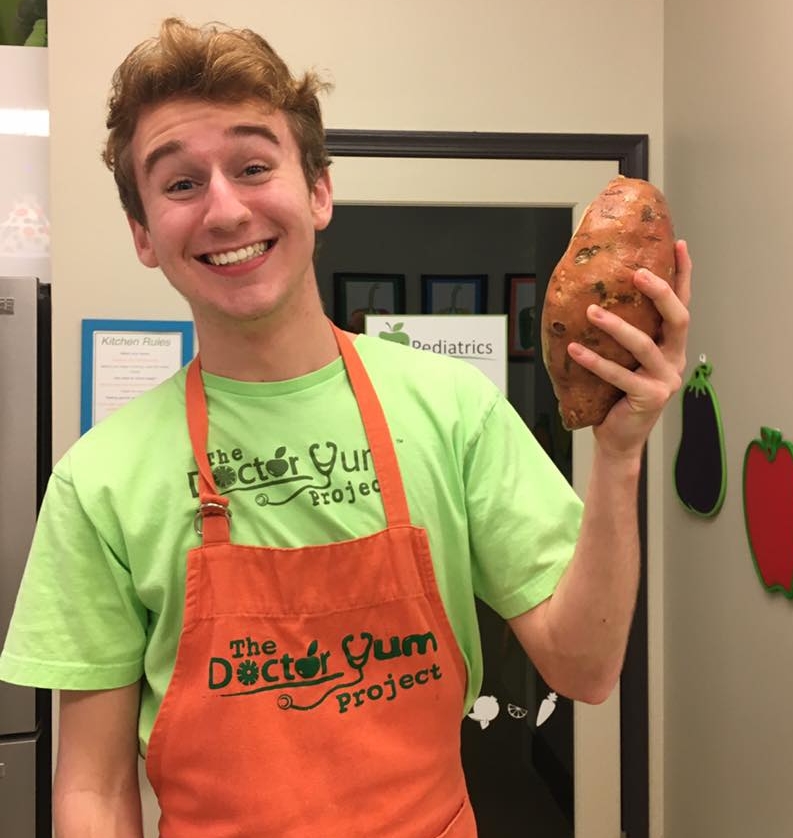

In Virginia, where I live, a project with a great name, the Dr. Yum Project, is all about teaching preschoolers and parents to get off to a healthy start with a curriculum that makes cooking and learning about food an adventure. The nonprofit, which is the brainchild of pediatrician Nimali Fernando, also features a “meal maker machine” to help busy families solve the perpetual problem of what’s for dinner with healthy recipes to prepare together.

Okay, now I’m hungry. Time to look for some carrots and blueberries to replace those oreos that are whispering my name . . .

If you’re interested in the topic of kids, health, and food, you might want to take a look at these articles, blog posts, and other resources:

- Farming with Young Children, by Katherine Patton, AltEdAustin blog

- Holistic Eating, Playing, and Learning Make for Healthy Kids, about Integrity Academy, AltEdAustin blog

- Researchers to Bring School Gardens, Cooking Classes to Austin-Area Schools, UT News

- Healthy Eaters, Strong Minds: What School Gardens Teach Kids, NPR News

- National Farm to School Network (Texas Program, based at the State Department of Agriculture)

- TXSprouts (Austin-area schools), a research project supported by the National Institutes of Health, focused on improving the health and nutrition education of elementary schoolchildren

Shelley Sperry