Big learning in miniature

/Every Thursday students at the Austin EcoSchool play the Game of Village, a complex, thoughtfully structured, open-ended game in which “children explore the world at large by creating a world in miniature.” Throughout the school year, they establish and run a society, take on individual jobs, and work together to form a government; together they solve problems major and minor— all on a scale of 1:24.

The geographic setting and time period change each school year. This year the game has taken place in ancient Egypt, under the tough scrutiny of Queen Cleopatra and her Roman spies. The Villagers—tiny figures called Peeps that the students create, complete with well-developed personalities, social and economic roles, and personal histories—spend their time building and maintaining homes, businesses, and public institutions. In the process, the students learn heaps of history, economics, physics, math, art, writing, and many practical life skills.

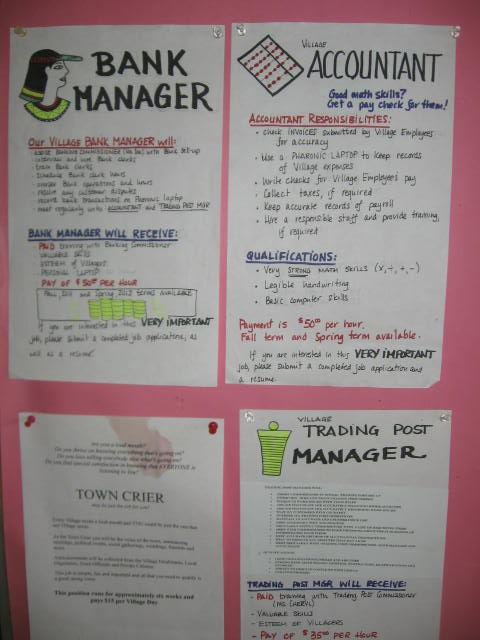

When I visited the school one Thursday morning earlier this semester, it was buzzing with activity. Students were applying for positions as town crier and managers of the trading post, bank, and post office. Outgoing managers were checking references of applicants and preparing to train the new employees in systems they’d developed over the course of the previous semester. Architects and engineers were finalizing construction plans for a mummification temple. An accounting team was processing invoices, issuing paychecks, and auditing the bank.

I asked one young accountant, a twelve-year-old named Holland, what she liked about the game and her (Peep’s) role in it. “Well, I don’t know any other kids my age who know how to balance a checkbook,” she said. With a smile of satisfaction, she added, “I also know how to make a spreadsheet.”

Cheryl Kruckeberg, the school’s director, serves with other faculty members as one of the Village Commissioners who periodically “squeeze the game” by scheming behind the scenes to create new situations or problems to be addressed. For example, in the early spring they nudged the Villagers along in their construction projects with a letter from Cleopatra announcing an imminent visit. “That lit a fire under them!” she said. The students finished most of their buildings before the royal visit in hopes that the queen would look upon their village with favor.

Cheryl said that the Game of Village “fits in with everything else the school is about”: making learning natural, relevant, and lasting through a cross-disciplinary and theme-based curriculum that empowers students to realize their own personal goals. Through extended play, students learn real-life lessons—many of them about themselves. After spending a semester as a bank clerk, one student may gain the skills and confidence to apply for the bank manager position next time. Another student doing the same job may experience that all-too-common sensation of being trapped in a demanding job with little room for creativity. Both lessons are equally valuable. As Cheryl said, “I am not banker material. I am a craftsman.”

This kind of self-understanding is something the school seeks to cultivate every day of the school week, and it can be seen in full blossom on Village days. Reflecting on speeches given by candidates and their nominators about their qualifications for office before the Peep government elections, Cheryl wrote on the Village Blog:

This was just one of the many times that I have wished that you parents could be a “fly on the wall.” To hear these amazing young people acknowledge themselves and each other for such qualities as honesty, compassion, diplomacy, visionary thinking, and all the rest was beyond description. I walked away inspired that these are the ones to whom our future belongs.

You and your family can experience the miniature world of the EcoSchool’s Village at its sixth annual Mini Fair on Thursday, May 24, 5:00 to 7:30 pm. Students sell Mini Fair tickets, much like carnival tickets, up front, and you can use them to make your own Peep and take it on miniature rides or exchange them for snacks and various Peep goods. Tickets can be purchased with cash or traded for gently used books, pet supplies, or canned goods, which will be donated to local nonprofit organizations.