Learning to document children’s learning (Part 1)

/A key element of the Reggio Emilia–inspired approach practiced in a number of Austin alternative schools and preschools is the documentation of children’s daily experiences. In this three-part guest post, Marie Catrett provides a case study of the thoughtful and detailed documentation that occurs at Tigerlily Preschool.

This past January I reopened my in-home program, Tigerlily Preschool. I was excited to return to teaching and eager to bring something new to my work with children. Based on a mentorship that had begun in July 2011 with master teacher Sydney Gurewitz Clemens, I was certain that one of the new things I wanted to bring to Tigerlily was the practice of using daily documentation to record children’s learning.

When I made the decision to reopen Tigerlily, Sydney’s first question for me was: how do you plan to use documentation in your program? I wanted to pay attention to this particular group of children’s interests, teach with intention, connect families to our journey, and share my work with other folks who might be interested in a playful, creative, and expressive early childhood experience.

After each day of class, our families and Sydney receive an email that contains photos and conversations that reflect what went on in our classroom that day. Parents read “Our Day” with their children each evening, and together they talk about their child’s journey at Tigerlily. “Our Day” also resides in paper form in a notebook at school so that the children and I can refer to it and remember our history.

Elias is the quiet child in our group, talking most to the grownups in his world. The other kids like to talk to kids. Nayeli’s first words to me at an open house in December were: “Hello. I’m Nayeli. And you’re Marie. This is my new school and all my friends will be here. Oh look, you have animals!” She was not quite three years old. Off she went, creating habitats for tiny toy animals with the blocks, exuding confidence and enthusiasm. Elias was much, much quieter.

A few weeks into our time together, another child, Willa, asked Elias about wanting to play with a yellow toy hammer, a cherished item in our back yard. He replied to her and she came running back to me, remarking on the experience as a special one. “Elias gave me his words.” When Elias speaks, it feels special to me, too.

He is a kid who often prefers to start out watching from the sidelines, engaging in his own quiet play. I watched him, took photos, and tried to understand. Gathering data for documentation helped me to pay attention to the details of his behavior, to see what he was interested in, and to support that interest in our classroom.

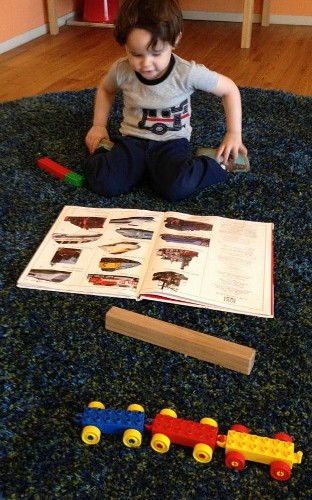

1/13

Elias spends a long time playing with a particular building block, moving it slowly back and forth in a way I’ve seen him move a Lego piece about. Later in the day I show him that particular block and ask him what it made him think about today.

Elias: Subway train!

Remembering that showing Elias the block prompted the train response to my question, the next day I make this invitation: “I’m going to read Freight Train over here. Anyone who wants to hear the story can come, too.” Elias joins us for story time for the first time.

The early weeks of school go by, and I am busy introducing the children to the workings of our new classroom. By mid-February I find I can easily pinpoint interests and activities that have excited each of the other children but am left scratching my head a bit with Elias. Following my lead, he has engaged in and explored many activities, but I don’t feel that he has truly arrived at his school.

2/22

What I most often see him do is carry around either the Lego train set we have, or a long wooden block, or two Legos held close together. He carries them, sometimes making a soft noise to himself. It is a modest activity but always seems to be much richer inside his head than what I see; he’s very focused. I plan to take some pictures of Elias doing this play throughout the morning today.

Elias: Reading Trains! There’s a snow train. There’s a Euro Star. It’s a subway train (the wooden block). Is there a passenger train?

Emerson: A mountain train, right there (in the book).

Elias: It’s a steam train (the blue, red, and yellow plastic train)!

Nayeli: A long, long steam train.

Elias: It (the steam train) has to pick up the passengers. It’s a snow train (the red and green Legos laid end to end).

Marie: Does the snow train make a sound when you play that?

Elias: Makes a quiet sound in the snow. Goes . . . (makes a very soft noise).

Sydney and I discuss what we see here. We are both very excited to hear so much language from Elias! I tell her how much I’d like to offer something that really speaks to him, and she wonders if there might be a train station that we could visit.

2/24

Elias returns to the train book, sparking interest from Willa and Nayeli as well.

Elias: (excited, to me) Reading Trains. Look at the wheels (touches the wheels on the toy train and the wheels on the train pictures in the book). (Monorail trains) are upside down trains!

Willa: There’s a train in his hand. Elias is playing with the train.Willa asks to see the model, takes a look, and then passes it back to Elias. I hear talk throughout the day from the other kids about its lights and the windows.

Nayeli: The train is going choo-choo. I peeked in the windows.

2/28

Train play comes outside, too! For a second day Elias and Emerson spend a long time working to pile sand up under a corner of the sandbox.

Emerson: Making a fire, making a fire! There!

Elias: I’m stoking the fire. Where do you want to put the coal? Putting coals into the fire. Here comes the train! That’s part of the blue zoo train. On the track it moves. Trains move on their tracks.

Nayeli: I went on a train with my papa. I said “hi everyone!” when I was on the train.

Nayeli: (sings) Elias, Elias, you shine like a star.

Willa: (also sings) We love you Elias, just as you are.

Elias: I rode on a train outside.

Willa: Was it a monorail train?

Elias: Rode on a Mallard train. Mama rode with me. Went up in the passenger car.

3/1

Emerson: Made a passenger train.

Train interest is now very present in our classroom. The parents and I plan what will be the first of three visits to the Austin Amtrak station.

In our program, field trip experiences come in threes. The first visit lets the children focus on the magic of a new place: everything is new! If you see a ladybug on the sidewalk, well, perhaps that sidewalk always has a ladybug. A second trip allows us to test those initial impressions and gather more information. On a third visit, children have become experts about their encounter.

The children and I prepare for our first visit.

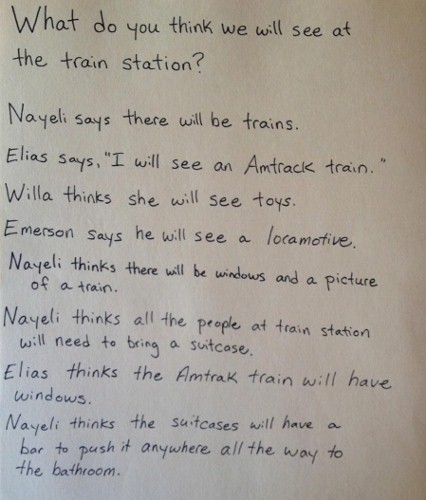

3/21

Emerson: I made trains!

We make a list of the things the children think they might see. I hope the list will help organize their interest on our visit.

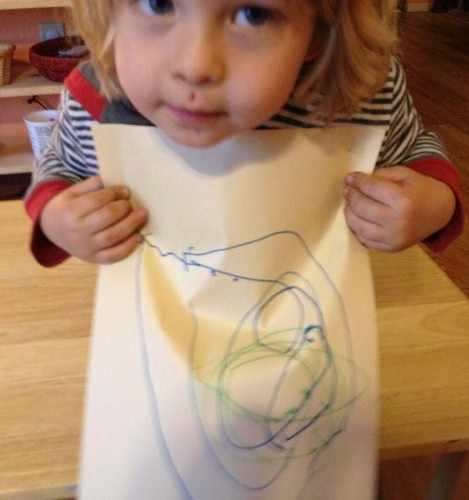

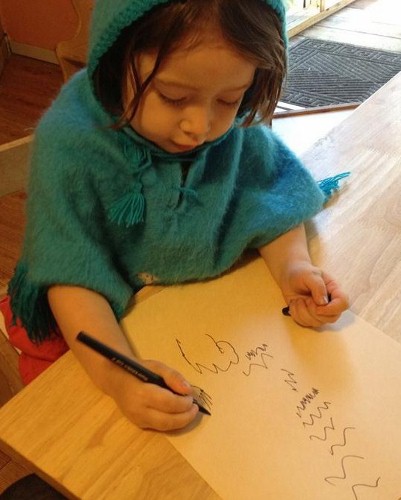

After making this list, Nayeli decides to make her own list. She sits down to write all the words the children have said.

Nayeli: I wanted to write down about what we had to say. First I draw pictures of the trains. Choo choo choo! (makes small circles going up on the top right). Choo choo choo! Choo choo choo! Okay, ah, we said . . . Emerson said . . . (makes left-to-right row of marks on the paper) he would see a locomotive (more marks). I don’t know what Elias said.

Marie: Would you like me to read it to you off of the list?

Nayeli: Yeah.

Marie: “Elias says I will see an Amtrak train” at the station.

Nayeli: (Writing) Elias said . . . I would see an Amtrak . . . at the station.

Elias: (Listening, also looking at the train book) That’s an Amtrak train!

Nayeli: I have ideas on my list. What did Willa say?

Marie: “Willa thinks she will see toys.”

Nayeli: (Writing) Willa thinks . . . she will see . . . toys. (Points to these new marks) This says Willa thinks . . . she will see . . . toys.

Elias: (Looking over the list with us) I will see an Amtrak train. It has windows.

Nayeli: What did Emerson say he thinks he will see?

Marie: (Reading) Emerson says he will see a locomotive.

Nayeli: Okay. (Writing) Emerson says he will see a locomotive. Anything else he said? Okay, anything that I said again?

Marie: Here’s what I have: Nayeli says there will be trains. Nayeli thinks there will be windows and a picture of a train. Nayeli thinks all the people at the train station will need to bring a suitcase.

Nayeli: Yeah, because you will need to pack up your things in it! And there’s a bar to push it where you want to go. If you push it all the way to the bathroom that will be really far!

Marie: Should we write that?

Nayeli: Yeah! (We both write on our lists.)

Marie: Are you finished? May I put your list next to mine?

Nayeli: I forgot to say conductor on it! Con-duc-tor. I write about conductor here. I will give this list to the conductor, so that way the conductor will remember what his name was on it.

To be continued in Part 2, coming June 21.

© Marie Catrett