The chance to feel frustrated

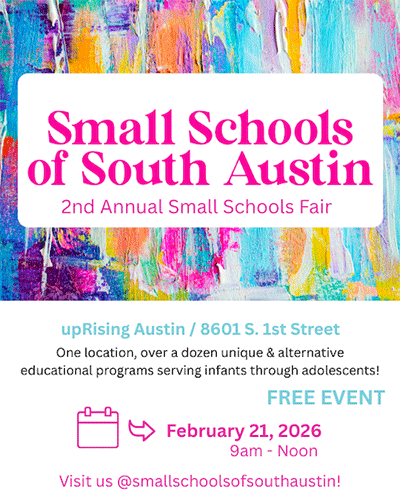

/I’m pleased to welcome the illustrious Kami Wilt, of the Austin Tinkering School and Austin Mini Maker Faire, to Alt Ed Austin’s lineup of guest bloggers. Here she discusses the challenges and rewards of frustration. She'd love to hear about your experiences, so I encourage you to leave Kami a comment or question below.

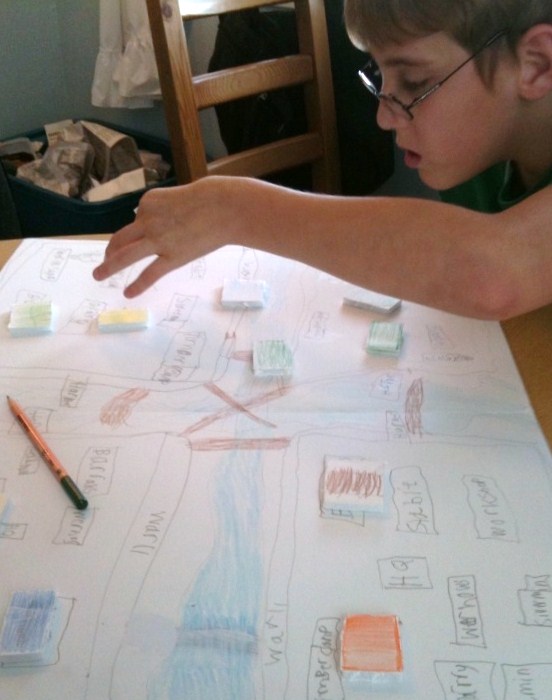

Recently I was leading a class and was, as usual, doing several things at once: plugging in the glue guns, showing someone how to test his battery with the multimeter, getting out the sharpies for the kid who has to decorate every inch of available space—the usual. This is the kind of usual that I totally love.

True to the tinkering ethos, we had an outcome in mind, but we left it open-ended as to how to arrive at that outcome. In tinkering, we try to create projects where kids are encouraged to design and create and problem-solve on their own. We consciously choose not to create too many projects (though sometimes they have their place) that are just follow-along-with-the-teacher activities (“Cut here, fold there, and now we all have a toy car that looks exactly the same! Wheee!”).

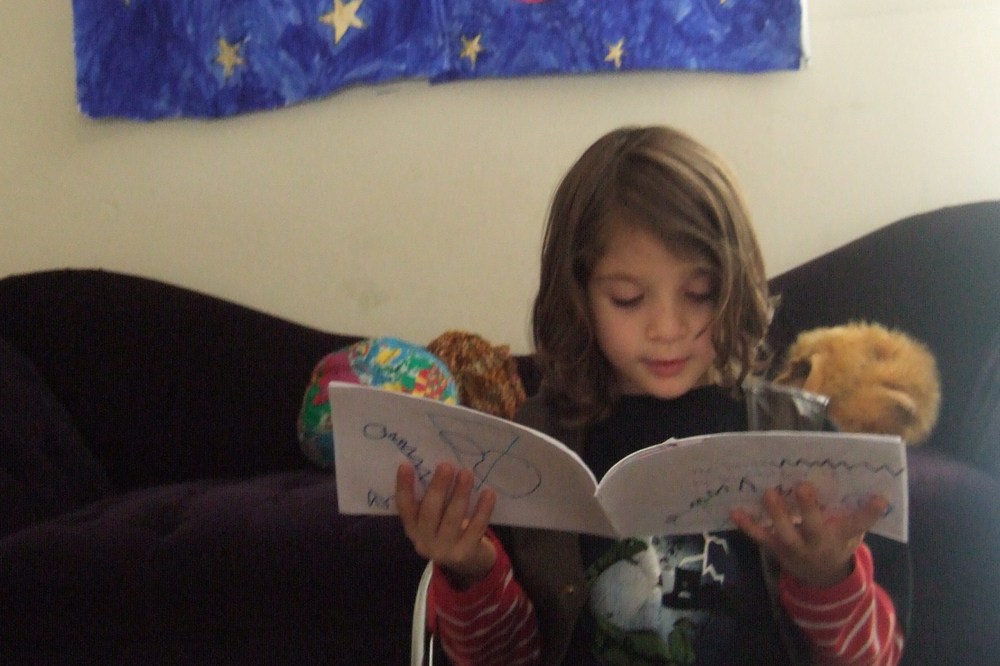

Anyway, I had a kid who was stuck. He hadn't been stuck for long. But he was stuck, and the expression on his face read, “Frustrated.” He was SO CLOSE, and I wanted so much to take his project out of his hands and just get it working for him. In fact, the urge to just get it going and spare us both the experience of feeling frustrated and stuck for even one second was almost unbearably uncomfortable. But I decided to ride it out for just a few moments more. Interestingly, he didn't disengage or walk away from the table. I stood next to him and quietly looked at his project with him. I didn't talk a lot or offer suggestions (and he didn't ask for any). I'm sure you can guess the moral of this story: After a few moments of rumination and meditation, the next step revealed itself. His excitement and ownership of the project were not infringed on by me, and now he has a cool experience in his memory bank of working through frustration successfully.

Why is it so hard for us to let our kids feel frustration? It makes me break out in an icy sweat sometimes, and I supposedly have experience in these matters. Luckily, I have my mentor, Gever Tulley, who created Tinkering School and Brightworks in San Francisco, to inspire me and keep me motivated to create experiences where kids have time and space to work on projects (and all the accompanying successes and failures) in their own way, free from an overabundance of adult imposition. An ability to manage and work through frustration is essential to almost anyone in our world who gets anything done. As I overheard one kid say to another recently, “A genius is someone who tries something and if it doesn't work out, he tries something else. And if that doesn't work out, he tries something else. And if that doesn't work out, he tries something else.” Couldn’t have said it better myself!

I think we disrespect children when we assume they can't handle a moment of frustration. It can be really beneficial for a child to have space to think through something on her own, without having an adult jump in and prod her along. We adults can at times be overzealous in our roles as supervisors and facilitators of experiences. As Gever said in one of his great TED talks, “We, the adults, are superheroes, endowed with the power of supervision. Let us use our powers wisely and be amazed at what children can do.”

Kami Wilt