Inspiring STEM learning in Austin youth

/Alt Ed Austin doesn’t often publish guest posts from representatives of large corporations, but both the local Girl Scouts and the Microsoft Store staff were so excited to share the fun learning they’ve been doing together that we couldn't help but pass it along. Guest contributor Marco Cervantes is the store manager of the Austin Microsoft Store at The Domain, which offers free YouthSpark summer camps.

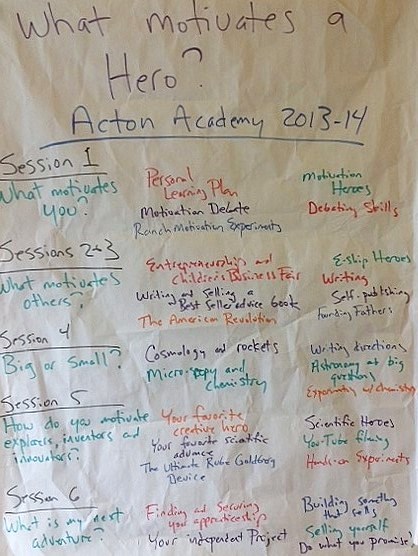

Brownies learn about the history of the computer to earn their “Computer Expert” badge in a recent workshop.

Brownies learn about the history of the computer to earn their “Computer Expert” badge in a recent workshop.

With all the available tech currently on the market, it’s easy for today’s youth to get sucked into a stream of unconscious thumb scrolling and finger tapping. As a manager at the Microsoft Store in Austin, I find frustrated parents sometimes pointing the finger at us, claiming that we are the source of their children’s lack of focus. However, our intention is quite the opposite. Microsoft is taking action to help involve today’s youth in meaningful and productive activities.

Amidst Austin’s booming tech scene, the next generation is deeply immersed in the digital world and will soon be the new employees managing projects and writing code. Yet these skills are seldom taught in elementary, middle school, and high school classrooms. To address this issue, the Microsoft Store at The Domain offers workshops to local youth to give them a head start in the fields of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM).

The Girl Scouts of Central Texas (GSCTX) is one of the many nonprofit organizations we have partnered with in the Austin area since the store opened in April 2012. To help meet the growing demands for hands-on STEM learning and to provide increased opportunity for girls, Microsoft has donated more than $500,000 in software to GSCTX. We host merit badge workshops two or three times a week for the Girl Scouts to teach them about internet safety, apps, and more. We extend free instruction to GSCTX staff members as well, with dedicated sessions to share Windows and Office proficiency tips so they can better organize and lead their troops.

“We strongly believe that investing in today’s youth and providing opportunities beyond the classroom are some of the most beneficial ways we can help set up the girls for a successful future,” says Lolis Garcia-Baab, director of marketing and communications at GSCTX. “We are helping to create the female leaders of tomorrow. By offering an outlet for youth to learn about technology, we are empowering them to reach their full potential, which may not be possible in many traditional classrooms.”

Microsoft’s dedication to helping the next generation extends far beyond the store walls. In addition to donations, our companywide YouthSpark initiative aims to create opportunities for 300 million youth around the world, including 50 million young people in the United States, by 2015. Through partnerships with governments, nonprofit organizations, and businesses, we connect them with education, employment, and entrepreneurship opportunities. For example, through our DreamSpark program, students gain access to professional developer and designer tools at no cost so they can get a head start on their careers or create the next big breakthrough in technology.

We are excited to help Austin youth create the world they want tomorrow, starting today. To learn more about Microsoft’s community and educational activities in Austin, please visit the store website.

Marco Cervantes