Celebrating failure!

/In this very personal guest post, Ariel Dochstader Miller argues for embracing failure as a positive and necessary experience in school and beyond. Ariel is cofounder and chief motivator at Austin’s Bronze Doors Academy.

My birthday was a few days ago, and my husband fulfilled my lifelong dream of having a party for me at Peter Pan Mini Golf. One of the partygoers was my eight-year-old birth daughter, whom I carried for my dear friend, who is infertile.

At one point during the party, her mom told me that she was very upset and crying because she was not doing well at mini golf. I went to her and discussed how she was feeling. This child was crying and wanted to leave because she was not performing up to her expectations.

One of my concerns for this child of my heart is that she is becoming a perfectionist because she is attending a school where the factors that determine success are all external. She is living in a world that values a memorize-for-the-test-then-forget mentality versus learning how to fail fabulously and celebrate learning because it is fun. The other young party attendees were students who attend the progressive school I own. None of them were keeping score, and I could tell the amount of fun they were having by the peals of laughter issuing forth from the golf course.

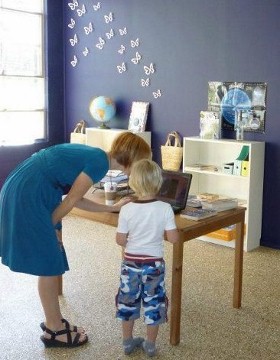

Bronze Doors Academy kids celebrate the prospect of failure at the mini golf course on this special occasion—and at school every day.

Bronze Doors Academy kids celebrate the prospect of failure at the mini golf course on this special occasion—and at school every day.

One of the things I fear most for public school youth (and those at many traditional private schools as well) is that too often they are taught that failure is the worst thing that can happen. I could not disagree more. I believe failure should be celebrated. Milton Hershey started seven businesses that failed before he found his recipe for success in his hometown of what is now called Hershey, Pennsylvania. Walt Disney went to more than three hundred banks before he found one that would fund his dream of Disney Studios. How many people would have stopped at one or two failed attempts?

The determining factor for today’s students’ future will not be how many degrees they have, their test scores, or grades but rather their entrepreneurial skills and ability to think critically. Microsoft specifically says it hires people who fail often because that means they are innovators who are not afraid to push the boundaries of whatever they are working on.

Both of my parents died young, and thus I am a huge joy advocate. None of us knows how much time we have, so why waste it not experiencing joy because we are not performing to some external measure? At Bronze Doors Academy, the adults model the attitude that failing can be spectacularly fun and is actually quite important, because it means you are stretching yourself and trying something new and different. We also model that perseverance is much more desirable than striving for perfection. In my study of business and owners of successful companies, I have found that their unwillingness to give up was much more important to their success than their grades. A study I read a few years back found that most successful business owners were C students.

Solving the problems we are facing as a society will require serious out-of-the-box thinking. Why not enjoy ourselves while pushing the boundaries of what we know is possible, even if it means the ball never goes in the hole?

Ariel Dochstader Miller