When learning gets messy: The power of productive struggle in early elementary

/The Compass School is a research-driven school in Austin that grounds its educational approach in neuroscience, psychology, and education research. Anna Yakabe, a founding member and Director of Learning, shares insights from their Innovation Lab, where young learners develop the perseverance and problem-solving skills needed to create meaningful change.

In Hidden Potential: The Science of Achieving Greater Things, Adam Grant reminds us that the real magic of learning comes from the struggle.

Grant describes learning as a journey shaped by how we respond to challenges. When children wrestle with something new, they're strengthening the neural pathways in their brains that lead to long-term understanding and resilience. Each mistake, frustration, or I-don't-get-it-yet moment is an invitation to stretch the mind and build perseverance.

This concept of productive struggle has deep roots in education research. J. Hiebert and Douglas A. Grouws introduced the term in 2007, though it wasn't until H. K. Warshauer's 2011 paper that it gained widespread recognition within mathematics education. The concept draws on several foundational frameworks, including Bjork's theory of Desirable Difficulties and Vygotsky's Zone of Proximal Development. These frameworks share a common insight: learning happens most powerfully in a particular space. When tasks are too easy, students experience boredom and minimal growth. When tasks are too difficult, students experience frustration and disengage. Productive struggle exists precisely in that sweet spot where the challenge is significant enough to require effort and creative thinking, but not so overwhelming that it becomes counterproductive.

While Warshauer's work focused on mathematical thinking, the principles of productive struggle apply across disciplines. The question that matters most to educators and parents is: What does this actually look like in a classroom with six- and seven-year-olds?

From Theory to Towers: Design Thinking in Action

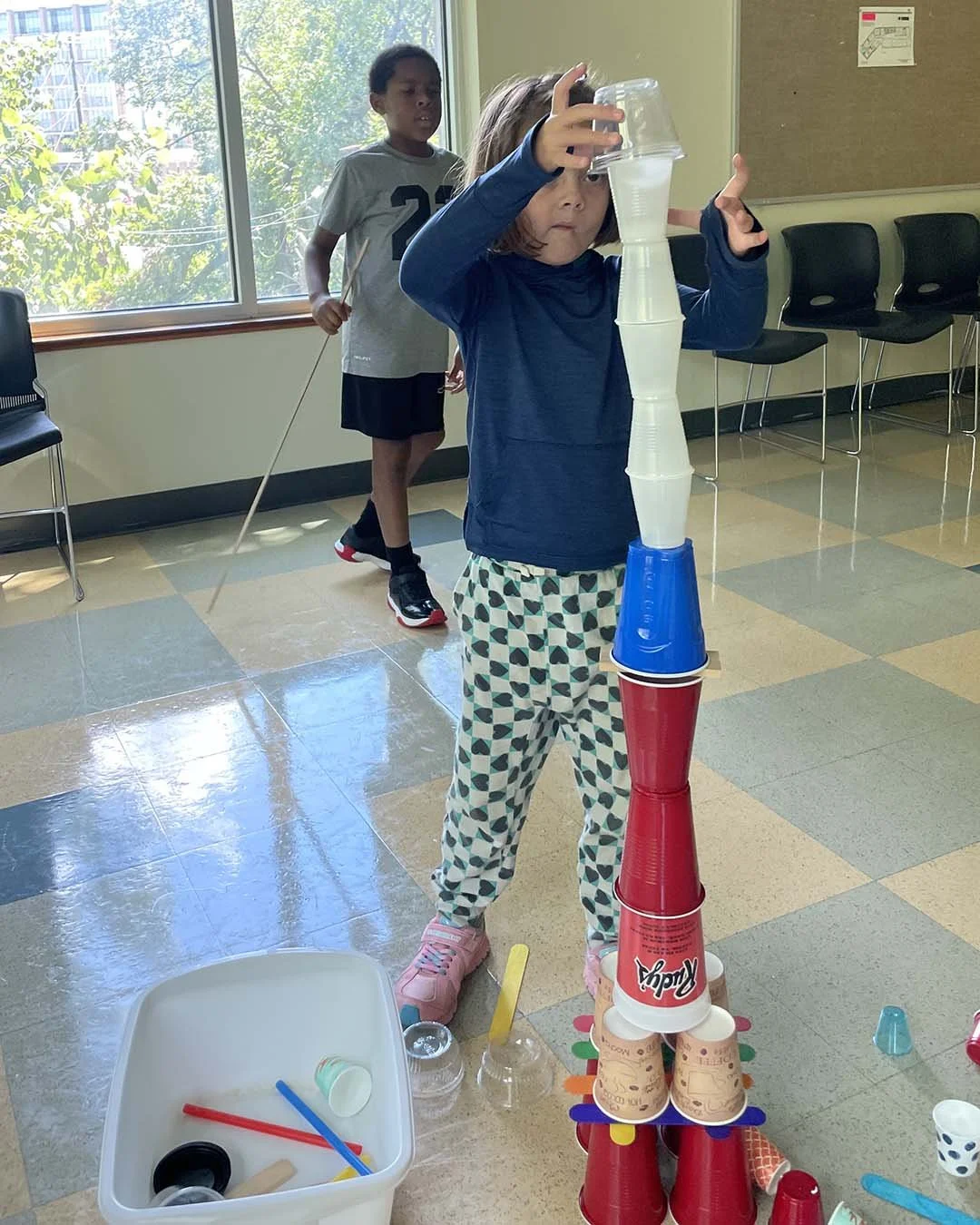

Recently, our young learners faced a challenge in our Innovation Lab that brought these research insights to life. The task: design a structure out of different size plastic cups for a LEGO person that stands at least 39 inches tall and can withstand a wind gust from a fan.

After a quick prototype and testing, students found that the fan caused structures to collapse instantaneously. One student captured the moment perfectly: "There needs to be weight to give it stability." This observation marked the beginning of their productive struggle.

The Messy Middle: Where Real Learning Happens

What unfolded over the next three days wasn't a neat path from problem to solution. It was iterative, frustrating, and essential to deep learning.

Students brainstormed: How can we add weight? They tried tape, hoping adhesive strength would compensate for structural weakness. They experimented with stacking cups of various sizes and materials, testing whether diversity in their building blocks would create stability. They placed LEGOs at the base, reasoning that a heavy foundation might anchor the entire tower.

Each attempt taught them something. Each failure led them to a revised design. This is the design-thinking protocol in its most authentic form—not a worksheet about problem-solving, but the actual experience of wrestling with a real challenge that has no predetermined answer. Students moved through cycles of defining the problem, generating ideas, prototyping solutions, and testing their effectiveness.

The breakthrough came from an unexpected place. What if the weight didn't need to be at the bottom? What if it could wrap around the structure like a sleeve? Students created a square LEGO structure that slid over the third cup from the bottom, adding stability exactly where the tower needed it most.

When the fan finally turned on and the towers stood firm, the celebration wasn't just about success. It was about the journey they'd taken to get there.

The Role of the Educator in Productive Struggle

During the cup tower challenge, no adult handed students the answer. No one told them where to place the LEGO sleeve or which cup would provide the best anchor point. Instead, educators asked questions: What happened when you tried that? What might you do differently? What are you noticing about the structures that are more stable?

The role of the educator is not to eliminate struggle, but to make it productive. Educators provide scaffolding through questioning rather than direct instruction, supporting students' thinking without removing the challenge that makes learning meaningful.

Why Productive Struggle Matters More Than Ever

Progressive education has long understood what neuroscience now confirms: Children learn best when adults support them through obstacles.

The research is clear. When students engage in productive struggle, they develop a growth mindset. They begin to see difficulty not as a stop sign but as a signpost pointing toward growth. They build executive function skills like planning, flexibility, and self-monitoring. Most importantly, they develop the courage to try, fail, and try again.

According to neuroscience research, when students work through challenging problems, they are building and strengthening neural connections. The effort required creates deeper, more durable learning than passive reception of information. This aligns with Grant's emphasis that achievement isn't about having the most natural ability but about developing the character skills that help us unlock our potential. Those skills—perseverance, adaptability, creative problem-solving—are built one productive struggle at a time.

Building Courageous Learners

When we give young children the space to struggle productively, we're not just teaching them about engineering or physics. We're teaching them about themselves. We're showing them that they are capable of facing uncertainty, of persevering through frustration, of collaborating to solve problems that no single person could tackle alone.

The next time you see a child wrestling with something difficult, resist the urge to jump in with the answer. Instead, lean into the discomfort. Ask a question. Express curiosity about their thinking. That struggle is not a problem to be solved. It's the very place where learning comes alive.

—Anna Yakabe | The Compass School